Gene therapy for corneal blindness: Light at the end of tunnel?

India-born biomedical researcher Rajiv Mohan working in USA's University of Missouri is pursuing a singular mission: bring sight to the sightless. He has developed a way to genetically alter a pathway that limits the amount of light that enters the eye and help cure corneal blindness. Ralph Chapoco, Sean Na and Karina Zaiets report from USA with Godhuly Bose from India

Growing up in India, Professor Rajiv Mohan learned to treasure the gift of sight as he watched relatives struggle to see. Three uncles, three aunts and a grandfather have suffered with eye problems, including blindness.

“They have double vision. They have myopia, hyperopia, things like that. It is all connected with the cornea. It is all preventable and treatable,” Mohan said. “I wanted to do something where I could make a difference.”

So he became an biomedical researcher, moved to the United States and pursued a singular, global mission: To help bring sight to the sightless.

As a University of Missouri professor and researcher, Mohan has developed a way to genetically alter a pathway that limits the amount of light that enters the eye -- in effect bringing light to the darkness.

Prof Mohan with his fellow researchers working on gene therapy at University of Missouri in USA

Prof Mohan with his fellow researchers working on gene therapy at University of Missouri in USA

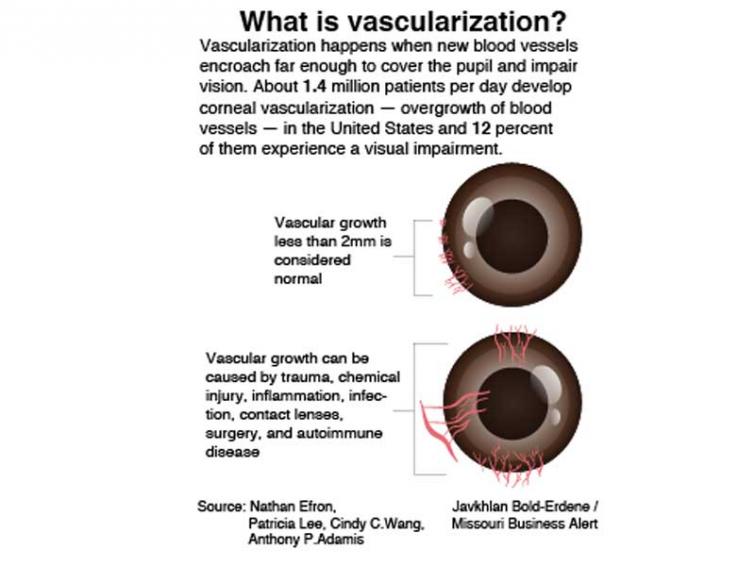

He seeks to treat a disability called “corneal fibrosis” or “corneal vascularization,” variations of a common eye problem. According to a review article published in the journal Eye and Vision, corneal disease is the third most frequent cause of blindness in the world. An estimated 1.4 million people develop corneal neovascularization per year, and 12 percent of them go blind.

Vision problems are a big issue in developing countries, including Mohan’s homeland.

“Prevalence of corneal blindness in India ranges between 1.9 percent to 4.3 percent as reported in various studies,” wrote Bhavana Sharma, one of Mohan’s collaborators in India.

But though the research shows promise, it’s still in the early stages and must clear several regulatory hurdles.

So a treatment may be years away.

A love of the laboratory

Mohan was born, raised and educated in the northern part of India.

“When I was doing my masters, I saw people going into the lab,” he said. “It was always very intriguing to me, to watch them do what they are doing, late into the night, all the time. I asked them what they did, and that made me really interested in the area.”

He got a scholarship to pursue a doctoral degree.

An organic chemist by training, Mohan transitioned to molecular biology after receiving a post-doctoral research opportunity in the United States. After that, he received academic appointments at some of the leading eye research institutes in the country, including the University of Washington and Case Western Reserve University.

He joined the University of Missouri faculty a few years ago after receiving an offer from an administrator who wanted to enhance ophthalmology research.

Now, he works in a lab similar to the ones that fascinated him as a young man.

His lab is in the basement of the Veterans Affairs medical center in Columbia, Missouri, down a maze of hallways illuminated by fluorescent light. Along the aisles of the lab are long benches covered with research equipment and instruments.

From early morning to late evening, Mohan and his research colleagues mix liquids and push buttons on the equipment. Their goal: To understand corneal damage and find the best way to treat it

That damage interrupts the complicated process of sight. Vision involves light, with eyes controlling and directing light to a single point located at the back of the organ before transferring information to the brain.

“When (light) comes and enters the eye, it is first bent by the cornea shape,” said Dr. John Jarstad, an associate professor of clinical ophthalmology. “It passes through the cornea, through the pupil, which is made up of the iris muscle. It goes through the pupil, and then it is also bent again by the lens of the eye.”

From there, signals are sent to the brain via the optic nerve, which processes the information for vision.

The cornea can be damaged for several reasons, through physical damage or by chemical means, causing problems with vision. Issues can also arise as the body tries to repair the damage.

Gary Wunder, a member of National Federation of the Blind in USA

Gary Wunder, a member of National Federation of the Blind in USA

“A lot of times it is the healing, and the scar tissue that comes from healing, that really affects the vision the most,” Jarstad said.

Once the cornea is damaged, scar tissue forms. That scarring can limit the light that passes through the cornea, which limits vision.

“In general, you would see probably more than one million people who require some sort of treatment of the scarring related to vision loss in India,” said Arkasubhra Ghosh, one of Mohan’s collaborators there.

Treatments are available, such as using lasers to remove one layer of the eye with the scar tissue. Severe scarring sometimes warrants a transplant.

“The cornea transplant patient, they have to be seen regularly, every month or three months, at least twice per year, for the rest of their lives,” Jarstad said. “They can reject the cornea from another donor. If you can keep your own tissue, that is the best because that will not reject.”

Mohan’s treatment, meanwhile, is “endogenous,” relying on the healing power of the patient’s own body.

Treatment shows promise, borders on ‘science fiction’

Mohan’s treatment is based on genetics.

“Gene therapy is a type of treatment where we introduce a new gene or overexpress a gene, in other words take a gene that is normally present and make more of it, or potentially replace a defective gene, something that makes a broken product that doesn’t work properly and replace it with a new, functional protein,” said Jason Rodier, an assistant professor of clinical ophthalmology.

The foundation for any protein production process within living organisms is DNA, which is essentially a string of chemical designations providing an instruction manual for making different parts of an organism.

Mohan’s treatment would rewrite the instruction manual to limit the scar tissue limiting the amount of light passing through the cornea.

“It borders on science fiction,” Rodier said.

The treatment is showing promise in a preclinical setting, which involves using rabbits to mimic the disease and apply the treatment.

“We put genes in the healthy cells, which is nearby to those (injured) cells,” Mohan said. “These cells start producing extra amount of proteins which kills those cells...”

Gene therapy takes advantage of economies of scale. A single treatment can be used multiple times, meaning it can potentially help many people -- whereas transplants require procuring tissues from deceased donors.

Mohan’s research is now moving into human trials. He’s soliciting the help of colleagues in his native country, asking them to recruit patients and collect tissue samples.

“Our contribution to the project is to bring in the knowledge of how the molecular pathways work in human beings, the clinical knowledge of how the scarring happens and how the disease progresses,” Ghosh said.

When that’s done, they will begin developing treatments for patients — with the goal of eventually making them commercially available.

“I am hopeful that in the next four years, both phases will be successful,” Ghosh said.

Researchers then face another set of hurdles: rigorous clinical trials to ensure the treatment is safe. Those can take a dozen years.

Given this timetable, the treatment may not be available for two decades, if that.

Gary Wunder, a member of the National Federation of the Blind, said he’s glad the research is under way, but people living with blindness shouldn’t put their lives on hold.

“I think that we believe that anything that will help people get and keep their vision is a good idea,” Wunder said. “But too many people wait for these cures instead of taking advantage of the limited lifespan that they have to still be happy and productive, and not feel sorry for themselves.”

Gene therapy and Indian healthcare infrastructure

If the gene therapy method becomes widely available, then does India have the infrastructure to implement this? "Yes, there are places in India which do have the infrastructure," says eye specialist Dr Anup Goswami.

"However, cornea grafting is an old and reliable method. It has a good success rate. But Indian society has certain social and religious aspects which lead to many people not wanting to donate their eyes upon their death. Given the number of corneas that are needed, we usually have a huge shortage in donations," Dr. Goswami says.

"Many Jains tend to donate their corneas. Sri Lanka also has a high percentage of people donating their corneas. In many large hospitals in our country we actually have to import corneas from Sri Lanka."

"Even after performing the grafting operation in these cases we often find that a few months later their cornea turns white and they become blind. In such cases, we use a process called keratoprosthesis which involves using inorganic material to create a transparent cornea which can be implanted into the patient’s eye. This process is successful only to some extent. It is an alternative method of cornea grafting. Rather it is also a method of cornea grafting, but it is not human cornea, but an artificial thing," he explains.

According to eye specialist Dr. Bhaskar Roy Chowdhury, a lot depends on how infrastructure intensive gene therapy is.

"If it is merely a protein injection, then infrastructure wise it is nothing, there is no problem of access. It then depends entirely on the cost," he says.

Dr Bhaskar Roy Chowdhury treating a patient suffering from corneal problem

Dr Bhaskar Roy Chowdhury treating a patient suffering from corneal problem

SIDEBARS:

Cornea grafting is the main available, reliable treatment: Eye specialist Dr. Bhaskar Roy Chowdhury

What methods are currently available to treat patients with corneal fibroplasty or cornea vascularization?

Right now the only method is cornea grafting. Sometimes if the cornea is not too damaged then we use contact lenses to varying degrees of success. However, cornea grafting is the main available treatment which is reliable and successful. Cornea grafting is done to replace scar tissue. Cornea grafting may be a full-thickness graft which is ‘penetrative keratoplasty’. In layman’s terms, a full thickness graft means that all the layers of the cornea are replaced. The entire eyeball is never replaced. It is only the cornea, the central part of the cornea which is grafted. You take a disc out of the central cornea and you replace it with a disc from the donor tissue. If that disc that you are cutting and replacing is full thickness – meaning it has all the layers of the cornea – then it is a penetrative keratoplasty. But mostly in these patients, the innermost layer – the endothelium – is usually intact and not damaged or affected by diseased tissue. So you need to replace only the stroma and the epithelium. The epithelium in any case gets replaced by the host tissue. Even in a full thickness graft, over a period of time it is replaced. So the main issue is replacing the stroma which comprises the majority of the cornea, thickness wise. The stroma is the one that undergoes scarring. The epithelium and the endothelium do not scar. It is only the middle layer. So there are techniques called lamellar keratoplasty by which the central lamella of the stroma is replaced. Usually the entire stroma is replaced, but sometimes if the scarring is very anterior then you can do an anterior lamellar keratoplasty also. So this is called DALK (Deep Anterior Lamellar Keratoplasty). So penetrating keratoplasty and lamellar keratoplasty are the two main grafting for corneal scarring.

You explained that the corneal grafting method is mostly successful. If a gene therapy method is introduced, do you think it would be able to fulfil a need for an alternative treatment and therefore become a competitor to grafting?

That depends largely on the treatment itself. If the treatment is simple, does not require too much follow-up, then definitely it will be a competitor and it will replace grafting. But it has to fulfil all these criteria. Usually gene therapy is very expensive, whereas a corneal graft in India costs up to 700$. And tissue availability is also not an issue now. It was one about 5-10 years back, but now we have a surplus of tissues, we don’t have a tissue scarcity at all. If you take absolute statistics of the exact percentage of how many people are cornea blind and how many corneas are harvested, then there will be a shortage. But many of these corneal blind cases either don’t have access to healthcare or they are not fit for grafting. If in an urban practice setting I want to do a graft today, I can do it in 7 days. There is that kind of surplus. Now if you go by absolute statistics – as in there are this many blind people and this many corneas have been harvested, then you see a huge gap. But that gap is not true. Practically, it is not there. As far as I know corneas are no longer imported from Sri Lanka.

Cornea grafting and patient experience:

I see a lot better now, says Dr Roy Chowdhury's patient Dipayan Chakraborty after cornea grafting

I had an issue with my vision since birth. When I went for treatment at the L V Prasad Eye Institute in Hyderabad, I was told that I had a condition called congenital corneal dystrophy. Back when I studied in class 2 or 3, I had a lot of trouble seeing in daylight. It began right from the morning and as they day progressed, my vision cleared a little. At night I had much clearer vision. I went to get it checked by a local doctor in Tamluk, Purba Medinipur (West Bengal), where I lived, back when I studied in class 4. These local doctors looked at me and said that they had never seen or heard of my condition, and they could not understand what was happening to me or why. In the year 1999 or 2000 I went to the L V Prasad Institute, I was seen by their cornea specialist V N Rao. At first he told me that there was a problem in my cornea, and I might have to get a transplant in the future. He said that nothing could be done at that time, so I would have to live with my problem for a while. I faced my biggest problem in the year 2008, right before my school final exams. I had conjunctivitis in both my eyes. After that my problem started increasing exponentially. What used to be blurry vision in the morning became almost indecipherable, it would almost never become clearer, my eyes would be painful, red, and watery at all times. I could hardly see in daylight. The local doctors explained that since I had had an issue in my cornea to begin with, the conjunctivitis had greatly accelerated the deterioration of my eyes to the point where I would have to opt for a cornea transplant as the last resort. But I could not do it at that time because I had my Madhyamik exams. So I somehow fought through to give my exams and right after that I had cornea transplants done in both my eyes over the next two years – 2008 and 2009. I see a lot better now after the procedure. It is important to remember that I cannot expect to suddenly have perfect vision after undergoing such a surgery. However, compared to the incredible trouble I had before, I have to say that I see much better. I could hardly see at all before, I was almost blind – so for me, seeing how much I can see now is a lot. Now I can sit on the first bench in a class and very clearly see anything written on the board. It’s a heaven and hell difference really, if I compare how I see now to how I used to see.

(This story is part of a series of special reports on India and the U.S. undertaken by the University of Missouri Journalism students. It was overseen by Laura Ungar, Midwest Editor/Correspondent with the St. Louis bureau of Kaiser Health News, and journalist Sujoy Dhar, founder of the Indian news agency India Blooms News Service.)

Support Our Journalism

We cannot do without you.. your contribution supports unbiased journalism

IBNS is not driven by any ism- not wokeism, not racism, not skewed secularism, not hyper right-wing or left liberal ideals, nor by any hardline religious beliefs or hyper nationalism. We want to serve you good old objective news, as they are. We do not judge or preach. We let people decide for themselves. We only try to present factual and well-sourced news.