Fatima Shaik

Fatima Shaik India existed as the bright star, says American writer Fatima Shaik tracing her Bengal roots

Fatima Shaik, award-winning American writer, was till recently teaching in a college in New York. In search of her roots, a few years back she came to Kolkata, from where her grandfather had migrated to the US. This forms the core of a documentary The Bengali. In a tete- a- tete with Ranjita Biswas, Shaik talks about her work and her journey to India

Excerpts from an interview

Please talk a little about yourself

I grew up in New Orleans and live in New York. I am interested in historical legacies and culture, particularly the way people related to one another in the past across ethnic, geographic, and colour boundaries.

You are the protagonist of the documentary The Bengali directed by Kavery Kaul where it narrates your journey to find your roots by the river Hooghly. What triggered it?

My quest was not so much triggered as it was made more urgent and possible with meeting Kavery. You see, the story of my grandfather's immigration to America had been passed down in my family since the 19th century. It was a frequent topic of conversation over the family dinner tables in my house and those of my aunts. They had a longing to see Mohamed Musa’s native land in order to know him better. He had died in 1919 during their early childhood and there was no way any of his children could go back to India in those years. My father became a pilot from a desire to eventually fly to India. My aunt Haleemon Shaik Felton wrote a poem named India that appeared in 1941 in a book published by Xavier University of Louisiana. My aunt Noyemon Shaik Tio finished her novel called The Bengali in 1986 based on the courtship and marriage of her parents. It was only copyrighted and not published though. And after Hurricane Katrina in 2006, my father, the last of this generation, died. So when I met Kavery and told her these stories and she offered to take me to India for her film, I jumped at the chance to be the first in my family to transform this inherited longing into reality.

Fatima's ancestral house in Hooghly district of West Bengal

Fatima's ancestral house in Hooghly district of West Bengal

Why is it important for you to find your ancestry?

One reason that ancestry was important to me was my parents’ experiences and mine living in segregation in the United States. My family, like anyone mixed with African blood, was told that our entire legacy was slavery and that we were inferior. But we knew differently. India existed as the bright star just beyond the horizon where my family imagined no racial boundaries and a more prosperous life.

How did you feel after ultimately tracing the family roots to a remote Bengali village after encountering many disappointments?

I credit Kavery with finding the remote Bengali village out of the huge landmass of India with only my grandfather’s letter as a starting point and putting me onto the tasks of family research in the United States for her film and my nonfiction book. I was not disappointed with the connections I made while confirming my family’s oral history. I found the ship that brought my grandfather to North America, his death certificate, the location of his properties in New Orleans, the names of his compatriots, and more. I even connected with childhood friends, who I found out had Indian grandfathers too!

What was the reaction of your immediate family back home?

My family was thrilled to know that the oral history was true-that my grandfather had come from an area near the Hooghly River, and that he was a relatively prosperous man-none of which had been found in earlier documentation. My family and friends were very happy to see the beautiful film and the images of the people in his village.

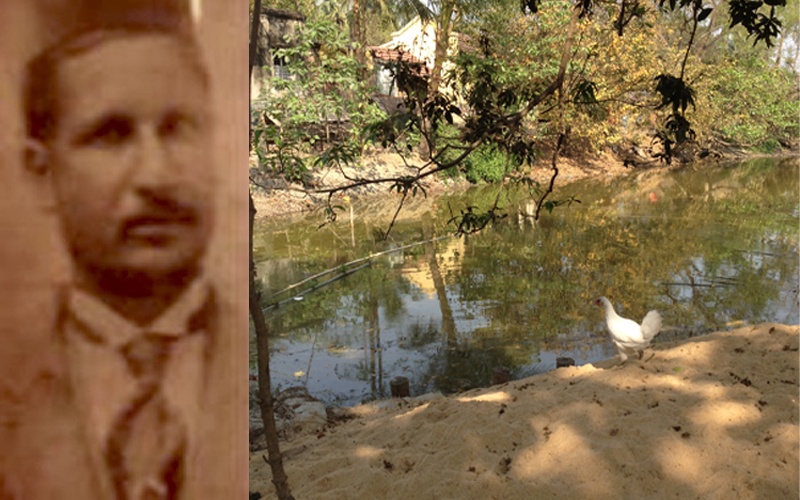

An image of Fatima's grandfather and her ancestral village in Hooghly district of West Bengal

An image of Fatima's grandfather and her ancestral village in Hooghly district of West Bengal

Your books also dwell on people of African descent in America. In this sense do you find resonance with writers like Alex Haley (Roots)?

Absolutely! I love the work Haley did at broadening the reach of the African American story to mainstream audiences. I also feel that Haley began a movement to make everyone consider their ancestral roots, especially the descendants of Africa who had contact with people from all over the world-as we now know with DNA. He popularised scientific and historical exploration, both of which are very important to me.

Tell us a little about these books, including Economy Hall for which you got multiple awards

Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood, published in 2021, was an American Book Award winner, the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities Book of the Year, and received a glowing review in the New York Times. Plus it was the nonfiction pick of the year in two book review journals, including Kirkus which gave it a starred review (a big deal in the publishing world). I’d like to be appropriately humble but it’s nice to have a 20-year project turn out right. The book is now in hardcover, softcover and Audible as an audiobook. I read it myself!

What are you writing now?

I am shopping around my family story that formed the basis of The Bengali film to agents and publishers. I am also writing about a New Orleanian whose father was from Italy and his mother was from Africa, This real-life protagonist left for Europe in the 1830s, became very wealthy, and was made an Italian count. There are so many good stories that no one knows but an examination of history will reveal.

(Fatima Shaik profile photo: Sophia Little Others: Fatima Shaik )

Support Our Journalism

We cannot do without you.. your contribution supports unbiased journalism

IBNS is not driven by any ism- not wokeism, not racism, not skewed secularism, not hyper right-wing or left liberal ideals, nor by any hardline religious beliefs or hyper nationalism. We want to serve you good old objective news, as they are. We do not judge or preach. We let people decide for themselves. We only try to present factual and well-sourced news.