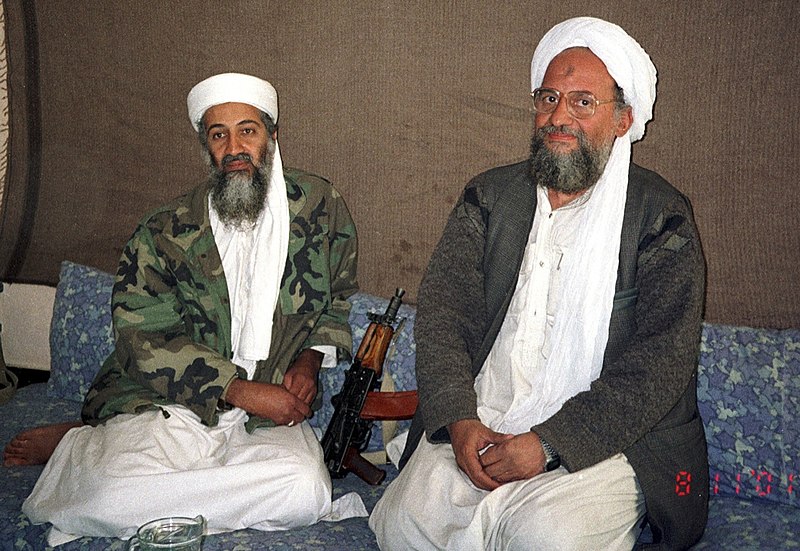

Ayman al-Zawahiri

Ayman al-Zawahiri Zawahiri’s killing in Kabul reiterates the hollowness of the Doha Accord and reignites the debate on Pakistan and terror

Al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri was killed in a United States (US) drone strike in Kabul on 31 July, and his killing marks the biggest blow to the terrorist group since its founder Osama bin Laden was killed in 2011.

Zawahiri had been in hiding for years, and a senior US administration official told reporters that the operation to locate and kill him was the result of “careful patient and persistent” work by the counter-terrorism and intelligence community.

The prospect of Pakistani involvement in Zawahiri’s targeting, meanwhile, has emerged as a contentious issue, even if neither the US nor Pakistan has so far publicly acknowledged such a role. If, indeed, there is truth behind reports suggesting that Islamabad did play a part, it will be yet another demonstration of Pakistan’s time tested policy of running with the hares and hunting with the hounds as far as terrorism and Rawalpindi’s terrorist assets are concerned.

Furthermore, more than two years after the US and the Taliban signed the Doha Agreement and almost a year after the radical Islamist group took over Afghanistan, Zawahiri’s killing in Kabul makes it evident that the peace deal the US had signed with the primary purpose of getting its troops out of Afghanistan is all but over.

Sadly, more than the US and the Taliban, the signatories of the Doha deal, it is the careworn people of Afghanistan who will yet again have to bear the consequences.

Ayman al-Zawahiri, a trusted lieutenant of Osama bin Laden, had played a key role in the 9/11 attacks and had later formed several of Al-Qaeda’s regional affiliates, including the one in the Indian subcontinent.

Since he took over as leader, Zawahiri has played the critical role in keeping the Al Qaeda together by working behind the scenes to forge consensus among Al Qaeda affiliates, branches, and franchise groups. His death is a massive setback for Al Qaeda, which has long been plagued by financial problems, limited command and control, infighting, and the lack of a geographical haven.

After Zawahiri’s killing, even Afghanistan will become dangerous territory for the group as it will henceforth undoubtedly hesitate greatly before trusting the Taliban. In many ways, Zawahiri’s killing is the second most significant blow to Al Qaeda after Osama bin Laden’s death, and it is one that the group may struggle to recover from.

As for how he was located and targeted, the New York Times, quoting official sources, revealed that Zawahiri’s ties to leaders of the Haqqani network “led US intelligence officials to the safe house” where he was hiding. The safe house was owned by “an aide to senior officials in the Haqqani network” in an area in the Afghan capital controlled by the Taliban. Senior Taliban leaders occasionally met at the house, the report added. It further disclosed that “Intelligence officers made a crucial discovery this spring after tracking Ayman al-Zawahri, the leader of Al Qaeda, to Kabul, Afghanistan: He liked to read alone on the balcony of his safe house early in the morning”. Otherwise, Zawahiri was “never seen leaving the house and only seemed to get fresh air by standing on a balcony on an upper floor”. This “pattern-of-life intelligence” gave the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) the opportunity during Zawahiri’s long balcony visits for a clear Hellfire missile shot “designed to kill a single person” and avoid collateral damage.

Convinced by the detailed intelligence briefings that he received on the proposed operation to take out Zawahiri, US President Joe Biden on 25 July authorized the CIA to conduct the strike “when the opportunity presented itself”, which it did on the morning of 31 July when a drone flown by the CIA found Zawahiri on his balcony.

The agency operatives fired the missile and hit the target, thereby bringing to an end a more than two-decade-long hunt. President Biden in a 1 August announcement informed that Zawahiri had been killed in an American drone strike, adding that “justice has been delivered and this terrorist leader is no more”.

The following day, Secretary of State Antony Blinken asserted, “By hosting and sheltering the leader of al-Qa’ida in Kabul, the Taliban grossly violated the Doha Agreement and repeated assurances to the world that they would not allow Afghan territory to be used by terrorists to threaten the security of other countries. They also betrayed the Afghan people and their own stated desire for recognition from and normalization with the international community”. Effectively ruling out any form of US recognition to the interim Taliban regime in the face of the Taliban’s “unwillingness or inability to abide by their commitments”, Blinken further said that the US will “continue to support the Afghan people with robust humanitarian assistance and advocate for the protection of their human rights, especially of women and girls”.

Zawahiri was nowhere near as high profile a target as Bin Laden had been for the US, just as the Al Qaeda of today is a pale shadow of what it was in its heydays, but his killing in Afghanistan is a significant achievement for the US.

It served to demonstrate Washington’s willingness and ability to continue to prioritize an old enemy, even if that was a mere individual, while simultaneously taking on challenges posed by some of the world’s largest and most powerful countries, Russia and China included. Moreover, in addition to eliminating a dangerous terrorist and helping bring some historic closure to the 9/11 attacks, the Zawahiri operation, as Shane Harris wrote in his article in The Washington Post, “also offered a proof of concept for the ‘over the horizon’ strikes Biden has long argued will let the United States stanch the threat of terrorism in Afghanistan without having to station troops there. The drone strike was the first in Afghanistan since US forces left the country a year ago”.

The Taliban, which found itself in a very tricky and vulnerable position especially given its acute yearning for international recognition, initially sought to suppress the news of Zawahiri’s killing.

The killing, perhaps, will actually be highly consequential for the Taliban as it will force the group’s leaders to reassess their relations with both the US and Al Qaeda.

It is also likely to intensify existing intra-Taliban rivalries and damage the Taliban from within.

The Taliban’s ministry of the interior, therefore, told the local Tolo news outlet on 31 July that a rocket strike had hit an empty house, causing no casualties.

The Biden administration, however, asserted that in the immediate aftermath of Zawahiri’s killing fighters from the Haqqani network had rushed his family away from the site and engaged in a broader effort to cover up his presence. US officials insisted that although no American personnel were on the ground in Kabul, “multiple streams of intelligence” had confirmed Zawahiri’s death. Two days later Taliban spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid issued a short statement accusing the US of violating “international principles and the Doha Agreement” and warning that such actions would work “against the interests of the USA, Afghanistan and the region”.

After deliberating at length at a high-level internal meeting on 3 August over the complex problems that Zawahiri’s killing had opened up for it, the Taliban was eventually ready to articulate its position on the matter only yesterday. It claimed in a statement that it “has no knowledge of the arrival and residence” of Zawahri in Afghanistan. The Taliban also sought to calm frayed tempers in Washington by assuring that “there is no danger from the territory of Afghanistan to any country, including America”. It is highly unlikely that either of these claims will be believed, not just in the US but across the international community.

Pakistan, whose role in stoking and flaming terrorism across the region is no longer hidden to anybody, has quite obviously figured prominently in the broader discourse over Zawahiri’s killing. Before taking a closer look at what experts believe Pakistan’s role in the matter was, it is worthwhile to point out that Zawahiri was reported to be living in Pakistan till the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, probably under the protection of the Pakistani intelligence agency the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI). The New York Times, for example, wrote that for many years it was believed that Zawahiri was hiding in the border area of Pakistan and it remains unclear why he returned to Afghanistan.

Following the withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan, it is believed that Zawahiri’s family returned to the safe house in Kabul. Reports quoting top intelligence sources have also claimed that Zawahiri was being sheltered in Karachi and that sometime after the Taliban takeover he was moved to Kabul through the Chaman border by the Haqqani network.

The fact that the Haqqani network, long known to be a terrorist proxy of the ISI, was involved in Zawahiri’s movements and his stay in Kabul is a clear indication of Pakistani complicity. Relations between the ISI and the Haqqanis have been so symbiotic that the then chief of the ISI, Faiz Hameed, had openly visited Kabul on multiple occasions after the Taliban takeover to weigh in for key ministries for the Haqqani network in the government that the Taliban was then engaged in negotiating and forming.

As per the leading Pakistani daily Dawn, Michael Kugelman, a scholar of South Asian affairs at the Wilson Center in Washington, brought up the possible Pakistani role in the killing of Zawahiri by saying, “I wouldn’t overstate its role, but also would take with some grains of salt the contention that there was no role at all”. Kugelman focused his attention on two possible forms of support – airspace and intelligence. The US was reportedly given “precise” intelligence about Zawahiri’s location, whether by the ISI or by disgruntled Taliban leaders. Kugelman asserted that “The geography doesn’t lie. If this drone was launched from a US base in the Gulf, it wouldn’t be able to fly over Iran. Flying over Central Asia is circuitous and hard to pull off if you’re undertaking a rapid operation.

This leaves the Pakistani airspace as the most desirable option for intelligence support and US officials have indicated the planning and surveillance for this operation took months. Could it do that all alone, with no on-ground presence?” Geo News, however, reported that Pakistan’s Interior Minister Rana Sanaullah had claimed that the drone had not operated from the country. The US has not released any details.

Michael Rubin, Senior Fellow at the American Enterprise Institute (AEI), is as convinced that Pakistan had a role in Zawahiri’s killing as he is that any such Pakistani role could not have been munificent or well meaning. He underlined on 2 August that “Pakistan’s economy is in danger, and the country is in danger of collapse. It was in this context that, last week, (Pakistani Army Chief) Gen. Qamar Javed Bajwa spoke to Washington to seek U.S. help to expedite the dispersal of a $1.2 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund. Pakistan needs the cash now to avoid default as its foreign reserves stand only at $9 billion, and its currency crashes.The question then is whether the White House, to its credit, played hardball and demanded a quid pro quo: U.S. support for Pakistan’s emergency loan in exchange for Pakistan giving up the location of Al Qaeda’s chief. That may sound like a good trade in the short term but it should also raise alarm bells”.

Rubin added, “While the State Department has long carried water for Pakistan despite that country’s terror support and pivot to China, rewarding Pakistan to the tune of more than a billion dollars for information on Zawahiri comes dangerously close to rewarding the country that once protected Al Qaeda founder Osama Bin Laden for its terror sponsorship. That may simply be realpolitik, but again it raises troubling questions: If the United States felt comfortable pressuring Bajwa to give up Zawahiri, then it suggests Washington long knew Islamabad’s complicity and yet, for two decades, did little to hold Pakistan to account. Likewise, if Bajwa is willing to betray Zawahiri, what other cards will the Pakistani military seek to trade in the future? Will it cultivate or protect Al Qaeda’s new leader? Shouldn’t Pakistan come in from the cold and sever all ties to Al Qaeda before they get a single penny of international assistance? In effect, shouldn’t Islamabad be forced to choose between Pakistan’s viability and its penchant for terror support? Also unclear is from where the drone flew that fired two missiles into Zawahiri’s residence. If the U.S. drone flew from Pakistan, then that would indicate Bajwa was even more complicit in Zawahiri’s death, but it would also suggest that Biden is allowing Pakistan a de facto veto over U.S. over-the-horizon counter-terrorism in Afghanistan”.

Persuasively describing Bajwa’s giving up Zawahiri as the equivalent of the head of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps betraying Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah to the Israelis, Rubin cautioned the Biden administration against “allowing Pakistan to profit from continued terror support”.

Whosoever it may be that was responsible for sheltering Zawahiri, and for getting him killed, the distressing reality is that the resulting likely consequence of an imminent deepening of Afghanistan’s isolation on the international stage is sadly going to be felt most by that vulnerable half of Afghanistan’s population that as per the United Nations World Food Programme is already experiencing acute hunger and is dependent on food supplies.

Support Our Journalism

We cannot do without you.. your contribution supports unbiased journalism

IBNS is not driven by any ism- not wokeism, not racism, not skewed secularism, not hyper right-wing or left liberal ideals, nor by any hardline religious beliefs or hyper nationalism. We want to serve you good old objective news, as they are. We do not judge or preach. We let people decide for themselves. We only try to present factual and well-sourced news.