Calendar

Calendar

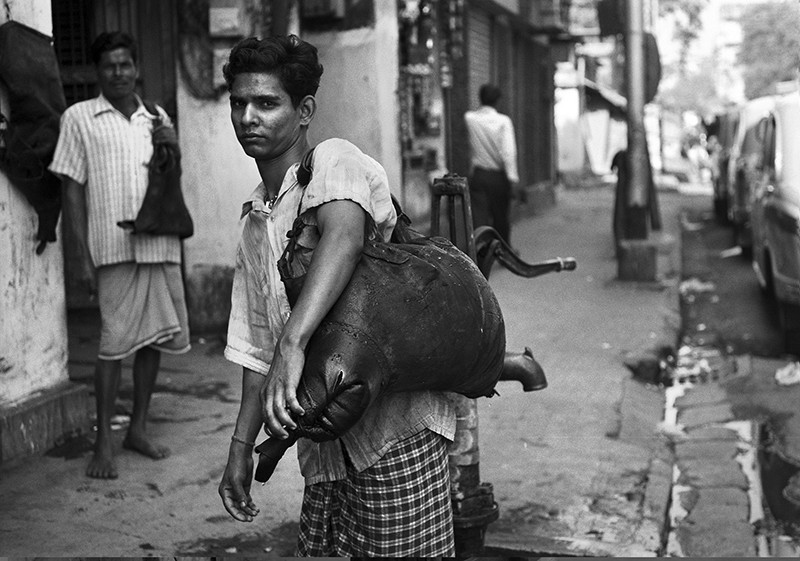

Kolkata Vistiwalas: The Last Bearers of Water

A special annual calendar by photographer Bijoy Chowdhury, gifted to friends and associates, captures Kolkata’s last remaining vistiwalas through his lens—preserving a vanishing profession and an essential fragment of the city’s living heritage for generations to come.

Kolkata has always carried its past lightly—sometimes in stone and mortar, sometimes in people.

Long before pipelines and plastic tanks, the city depended on human rhythm and muscle. Among these quiet lifelines were the vistiwalas, the traditional carriers of water, once an inseparable part of old Kolkata’s daily pulse.

In the early 1980s, they were everywhere. From dawn till dusk, men moved through narrow lanes and crowded crossings with a mashq—a water-filled goatskin bag—balanced across their shoulders.

Ripon Street, New Market, Bowbazar, Colutola Lane, Rafi Ahmed Kidwai Road, Bow Barracks and Sudder Street would stir with their presence as they supplied water to pavement eateries, roadside hotels and ageing buildings.

Their footsteps, soaked leather bags and measured pauses formed a rhythm the city barely noticed—yet depended upon.

The photographer met Sohel, one of the few who remained. "I met him on Ripon Street, where he spoke of arriving from Bihar as a child with his father, inheriting not just a livelihood but a way of life," Chowdhury says.

“There were once 70 or 80 of us,” Sohel said quietly. “Now there are only four or five.” Modern water supply systems, relentless physical labour and shifting dreams have ensured that no younger hands are willing to carry the mashq (practice) forward.

As the city accelerates, this slow, demanding profession fades into silence. What once felt ordinary now appears fragile, almost unreal. It is this moment—between presence and disappearance—that photographer Bijoy Chowdhury captures in his annual calendar.

Each year, Chowdhury chooses a unique, often overlooked subject rooted in Kolkata’s everyday life. This time, his lens turns toward the last vistiwalas.

These photographs do more than document faces and labour. They hold time still. They remember a profession, a gesture, a balance of body and burden that once quenched a city’s thirst. In doing so, the images become an archive of memory—an homage to a vanishing rhythm, preserved before it slips entirely into history.

(Bijoy Chowdhury is an award-winning photographer and documentary filmmaker. He can be contacted at bijoychow@yahoo.co.in)

Support Our Journalism

We cannot do without you.. your contribution supports unbiased journalism

IBNS is not driven by any ism- not wokeism, not racism, not skewed secularism, not hyper right-wing or left liberal ideals, nor by any hardline religious beliefs or hyper nationalism. We want to serve you good old objective news, as they are. We do not judge or preach. We let people decide for themselves. We only try to present factual and well-sourced news.